Relevant for Exams

Madras HC grants interim bail to 'Savukku' Shankar in 17 cases, citing abuse of process of law.

Summary

The Madras High Court granted interim bail to 'Savukku' Shankar in 17 criminal cases, with Justices S.M. Subramaniam and P. Dhanabal stating that repeated curtailment of his personal liberty constituted an abuse of process of law. This decision highlights the judiciary's role in safeguarding individual rights against potential overreach and is significant for competitive exams focusing on legal principles, fundamental rights, and judicial pronouncements.

Key Points

- 1The Madras High Court granted interim bail to 'Savukku' Shankar.

- 2The bail was granted in a total of 17 criminal cases.

- 3Justices S.M. Subramaniam and P. Dhanabal delivered the judgment.

- 4The court cited 'abuse of process of law' regarding 'repeated curtailment of his personal liberty'.

- 5The case pertains to the fundamental right to personal liberty.

In-Depth Analysis

The Madras High Court's decision to grant interim bail to 'Savukku' Shankar in 17 criminal cases is a significant pronouncement that underscores the judiciary's role as a vigilant guardian of individual liberties and the rule of law in India. This ruling, delivered by Justices S.M. Subramaniam and P. Dhanabal, highlighted that the 'repeated curtailment of his personal liberty' could only be construed as an 'abuse of process of law,' sending a strong message about the potential misuse of legal procedures.

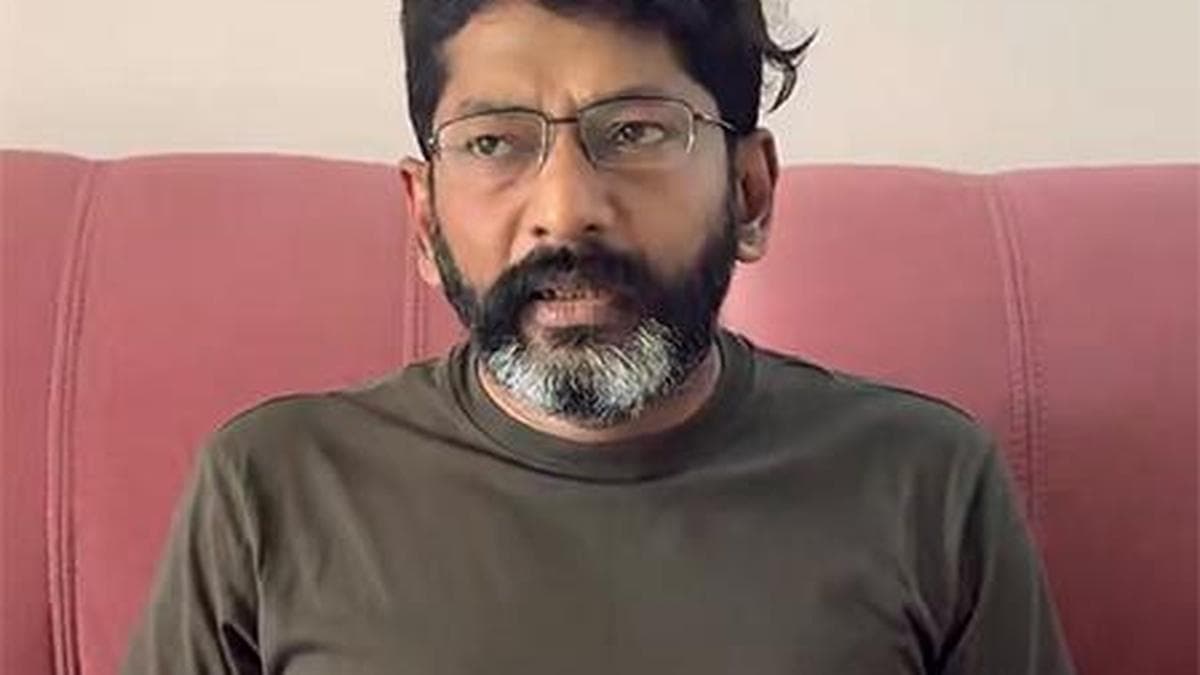

To understand the full import of this judgment, it's crucial to grasp the background context. 'Savukku' Shankar, whose real name is A. Shankar, is a former government employee turned independent journalist and political commentator known for his critical and often controversial exposes on politicians, bureaucrats, and the judiciary. His sharp critiques have frequently led to legal battles, including numerous defamation suits, contempt of court proceedings, and other criminal charges. Over time, a pattern emerged where he faced a multitude of cases across various jurisdictions, leading to a situation where his freedom was frequently jeopardized by arrests and prolonged legal processes. This particular instance saw him facing 17 separate criminal cases, an astonishing number that raised questions about the proportionality and intent behind such widespread legal action.

The core of what happened is that Shankar approached the High Court seeking relief from this barrage of cases. The court, in its wisdom, did not delve into the merits of each individual case at this interim stage but rather focused on the cumulative effect of these cases on his fundamental right to personal liberty. By granting interim bail, the court essentially acknowledged that while legal processes must run their course, they cannot be weaponized to perpetually restrict an individual's freedom, especially when it appears to be a concerted effort to silence dissent or criticism. The phrase 'abuse of process of law' is key here; it implies that the legal machinery, designed to deliver justice, was potentially being used for purposes other than its legitimate intent.

Key stakeholders in this scenario include 'Savukku' Shankar himself, as the petitioner whose personal liberty was at stake. The Madras High Court, specifically Justices S.M. Subramaniam and P. Dhanabal, represent the judiciary, which acted as the ultimate arbiter, upholding constitutional principles. The State and its various law enforcement agencies are also crucial stakeholders, as their actions in filing and pursuing these multiple cases were implicitly scrutinized by the court's observation. Finally, the public and media are significant, as this case directly impacts the broader discourse on freedom of speech, media independence, and the right to dissent in a democratic society.

This case holds profound significance for India. Firstly, it reinforces the robust constitutional protection of **Personal Liberty** enshrined in **Article 21** of the Indian Constitution, which states that 'no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.' The court’s intervention highlights that even a 'procedure established by law' cannot be abused to perpetually curtail liberty. Secondly, it touches upon **Freedom of Speech and Expression** under **Article 19(1)(a)**. While this right is not absolute and is subject to reasonable restrictions (like defamation or contempt), the sheer volume of cases against Shankar raised concerns about whether these restrictions were being used disproportionately to stifle critical voices. The judgment indirectly sends a message that the state must exercise restraint and avoid using the legal system as a tool for harassment.

Historically, Indian courts have often stepped in to protect fundamental rights against executive overreach, especially in cases concerning free speech and personal liberty. Landmark judgments, particularly after the Emergency era, have solidified the judiciary's role as a protector of civil liberties. This case builds on that tradition, demonstrating that the judiciary remains a vital check on power. The **Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC)**, which governs arrest and bail procedures, implicitly expects the process to be fair and just. The court's observation points to a potential deviation from this spirit.

The future implications of this judgment are manifold. It could serve as a precedent, encouraging other High Courts to scrutinize cases where individuals face an unusually high number of charges, particularly when these appear aimed at suppressing dissent. It may also prompt a re-evaluation by law enforcement agencies regarding the filing of multiple, repetitive, or arguably vexatious cases against critics. This decision strengthens public trust in the judiciary as an institution capable of safeguarding rights even against powerful state machinery. It underscores that while accountability is necessary, the legal process itself must not become a form of punishment, especially before conviction.

In essence, the Madras High Court's ruling on 'Savukku' Shankar is a powerful affirmation of India's commitment to constitutional democracy, where fundamental rights are paramount and the legal process must always serve justice, not become an instrument of oppression.

Exam Tips

This topic falls under 'Indian Polity & Governance' and 'Fundamental Rights' in UPSC/State PSC syllabi. Focus on Articles 19 (Freedom of Speech) and 21 (Personal Liberty) and their reasonable restrictions.

Study related topics like bail jurisprudence (types of bail, conditions for bail), contempt of court, defamation laws (IPC sections), and the role of the High Courts and Supreme Court in protecting fundamental rights. Understand the concept of 'abuse of process of law'.

Expect questions on the balance between fundamental rights and state restrictions, the independence of the judiciary, and the role of media in a democracy. Case-study based questions or direct questions on the interpretation of Articles 19 and 21 are common.

Pay attention to judicial pronouncements that define the scope of fundamental rights. UPSC often asks about the implications of landmark judgments on governance and civil liberties.

For Mains exams, be prepared to write analytical answers on topics like 'Judicial Activism vs. Judicial Restraint' or 'Challenges to Media Freedom in India,' using such cases as examples.

Related Topics to Study

Full Article

Justices S.M. Subramaniam and P. Dhanabal say that repeated curtailment of his personal liberty can only be construed as abuse of process of law