Relevant for Exams

Ganga Water Treaty (1996) between India-Bangladesh faces pressures, necessitating re-evaluation.

Summary

The Ganga Water Treaty, a 1996 diplomatic agreement between India and Bangladesh for sharing Ganga waters at Farakka, is now under scrutiny. Facing escalating hydrological, ecological, political, and geopolitical pressures, the treaty's re-evaluation is crucial for maintaining stable bilateral relations and ensuring sustainable water management in the region. This topic is significant for competitive exams focusing on international relations, geography, and bilateral agreements.

Key Points

- 1The Ganga Water Treaty was signed between India and Bangladesh in December 1996.

- 2The treaty specifically addresses the sharing of the Ganga River's waters at the Farakka Barrage.

- 3It was initially hailed as a significant diplomatic breakthrough for bilateral water management.

- 4The treaty has a 30-year validity period, meaning it is due for review or renewal around 2026.

- 5Current challenges include hydrological, ecological, political, and geopolitical pressures on the shared water resources.

In-Depth Analysis

The Ganga Water Treaty, signed between India and Bangladesh in December 1996, stands as a cornerstone of bilateral relations, specifically addressing the equitable sharing of the Ganga River's waters at the Farakka Barrage. Hailed as a diplomatic triumph at its inception, this 30-year agreement is now approaching its review period around 2026, facing unprecedented hydrological, ecological, political, and geopolitical pressures. Understanding its historical context, current challenges, and future implications is crucial for competitive exam aspirants.

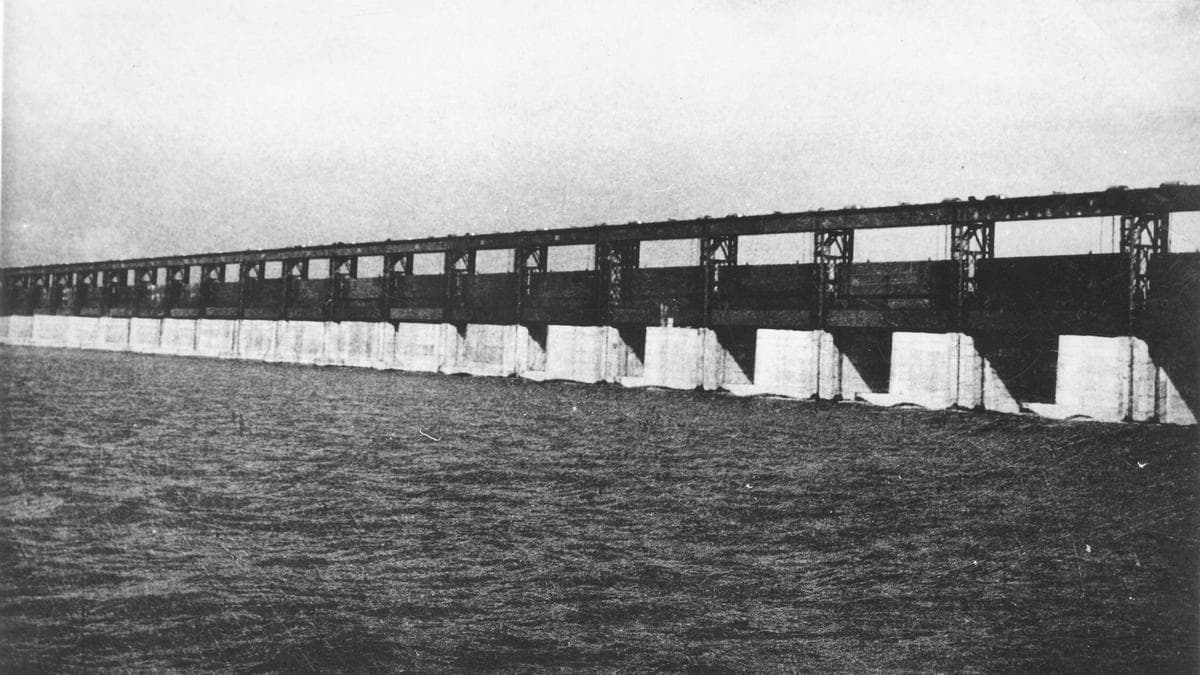

The genesis of the Ganga water dispute traces back to India's decision to construct the Farakka Barrage in the 1960s, which became operational in 1975. The primary objective was to divert a portion of Ganga's waters into the Bhagirathi-Hooghly river system to flush out silt and improve navigability of the Kolkata Port, a vital economic hub. However, this diversion raised serious concerns in Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, regarding reduced water flows, especially during the lean dry season (January to May). Bangladesh feared adverse impacts on its agriculture, fisheries, navigation, and an increase in salinity in its southwestern region, particularly affecting the Sundarbans mangrove forest.

Several short-term agreements and Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) were attempted post-1971, including a five-year agreement in 1977, and subsequent MoUs in 1982 and 1985. These often proved unsatisfactory due to their temporary nature and the failure to establish a long-term, mutually acceptable framework. The 1996 Treaty, therefore, was a significant breakthrough. It stipulated a formula for sharing Ganga waters at Farakka during the lean season, guaranteeing Bangladesh a minimum flow under certain conditions, and ensuring that neither country would take actions to reduce the flow of water to the other. This treaty brought a period of relative stability to a contentious issue.

However, the pressures on the treaty have escalated dramatically. Hydrologically, climate change has emerged as a major disruptor. Altered monsoon patterns, increased glacial melt leading to higher flows in some periods, and significantly reduced dry-season flows are stressing the river system. This variability makes the fixed sharing formula of the 1996 treaty increasingly difficult to implement effectively. Ecologically, the reduced dry-season flow has exacerbated salinity intrusion in Bangladesh, threatening the delicate ecosystem of the Sundarbans, a UNESCO World Heritage site shared by both nations, and impacting biodiversity and the livelihoods of millions. Politically, the treaty faces scrutiny from various stakeholders. In India, the West Bengal government often expresses concerns about its own water needs, while in Bangladesh, public sentiment and political parties frequently demand a more favourable sharing arrangement, especially given the perceived impacts on their populace. Geopolitically, the broader context of transboundary water management in the Himalayas, including China's upstream activities on rivers like the Brahmaputra, adds another layer of complexity, raising questions about regional water security.

The key stakeholders in this issue are primarily the governments of India and Bangladesh. Within India, the Union Government (Ministry of External Affairs, Ministry of Jal Shakti) is responsible for international treaties, but the West Bengal state government is a crucial stakeholder given its direct reliance on Ganga waters and the location of the Farakka Barrage within its territory. In Bangladesh, the central government and its various ministries dealing with water resources, agriculture, and environment are directly involved, representing the interests of its citizens, particularly farmers and fishermen. International organizations and environmental groups also play a role in advocating for sustainable water management and ecological preservation.

For India, the resolution of the Ganga Water Treaty issue is of paramount significance. Bangladesh is a critical neighbour, sharing a long border and playing a pivotal role in India's 'Neighbourhood First' policy and 'Act East' policy. Stable water-sharing agreements are essential for maintaining strong bilateral relations, fostering economic cooperation, and ensuring regional stability. Any unresolved water dispute can strain diplomatic ties, potentially impacting trade, connectivity projects, and security cooperation. Economically, the Ganga's waters are vital for agriculture, inland navigation (National Waterway 1), and industrial development in states like West Bengal and Bihar. Socially, the livelihoods of millions on both sides of the border depend on the river's health and equitable water distribution.

While the Ganga Water Treaty is an international agreement, India's internal constitutional framework for water management provides context. Water is primarily a State subject under **Entry 17 of the State List (Schedule VII)** of the Constitution, covering water supply, irrigation, canals, drainage, embankments, water storage, and water power. However, **Entry 56 of the Union List (Schedule VII)** empowers Parliament to regulate and develop inter-State rivers and river valleys if declared expedient in the public interest. This allows the Union government to legislate on inter-state river disputes, as seen in the **Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956**. Although the Ganga is an international river, the principles of cooperative federalism and balancing state and national interests are relevant to India's approach. India's **National Water Policy** also emphasizes integrated water resources management and the need for optimal, sustainable, and equitable use of water.

Looking ahead, the renegotiation or review of the 1996 Treaty around 2026 presents both challenges and opportunities. A simple renewal might not suffice given the changed hydrological realities. There is a strong case for moving towards a more comprehensive, basin-wide management approach that goes beyond mere flow sharing. This could include joint initiatives for flood control, drought management, data sharing, climate change adaptation strategies, and cooperative projects for river dredging and ecological restoration. The outcome will significantly shape India-Bangladesh relations for decades and could set a precedent for managing other transboundary rivers in the region, such as the Teesta and Brahmaputra. A collaborative, science-based, and forward-looking approach is essential for both nations to ensure water security and sustainable development in the face of growing environmental pressures.

Exam Tips

This topic primarily falls under GS Paper II (International Relations, Bilateral Groupings & Agreements, India and its Neighbourhood) and GS Paper I (Geography - Indian Rivers, Water Resources, Climate Change Impact) for UPSC. For State PSCs, it's relevant for Indian Geography and Current Affairs.

When studying, focus on the historical timeline of the dispute, the specific provisions of the 1996 Treaty, the geographical context (Farakka Barrage, Ganga basin, Sundarbans), and the multi-dimensional challenges (hydrological, ecological, political, geopolitical). Be prepared to discuss the significance for India's foreign policy and regional stability.

Common question patterns include: 'Critically examine the challenges facing the Ganga Water Treaty and suggest measures for its effective renegotiation.' (Mains); 'Discuss the significance of the Ganga Water Treaty for India-Bangladesh relations.' (Mains); 'When was the Ganga Water Treaty signed?' or 'The Farakka Barrage is located on which river?' (Prelims).

Understand the distinction between inter-state river disputes (within India) and transboundary river disputes (with other countries) and the relevant constitutional provisions that apply to each.

Pay attention to the role of climate change as an escalating factor in water disputes and how international agreements are adapting to these new realities.

Related Topics to Study

Full Article

Once hailed as a diplomatic breakthrough, the Treaty now faces mounting pressures – hydrological, ecological, political, and geopolitical