Relevant for Exams

TN AG tells HC no empirical data on Thirupparankundram stone pillar being a 'deepathoon'.

Summary

Tamil Nadu Advocate-General P.S. Raman informed the High Court that the State lacks empirical data to prove a stone pillar on Thirupparankundram hill is a 'deepathoon' and thus declined to take a definitive stand. This highlights challenges in classifying historical structures without conclusive evidence, making it relevant for state-level exams focusing on cultural heritage and legal proceedings concerning archaeological sites.

Key Points

- 1Advocate-General P.S. Raman represented the State of Tamil Nadu in the High Court.

- 2The legal matter concerns a specific stone pillar located on Thirupparankundram hill.

- 3The State informed the High Court that no empirical data is available to prove the pillar is a 'deepathoon'.

- 4The State explicitly stated it had not formed an opinion and did not wish to take a stand on the matter.

- 5The context is a legal proceeding in the High Court regarding the classification of a historical structure.

In-Depth Analysis

The recent statement by the Tamil Nadu Advocate-General P.S. Raman in the High Court regarding a stone pillar on Thirupparankundram hill underscores a critical challenge in India's efforts to preserve and classify its vast cultural heritage: the lack of empirical data for historical structures. This case is not merely about a single pillar; it highlights the complexities of archaeological identification, legal interpretation, and the state's role in safeguarding our past.

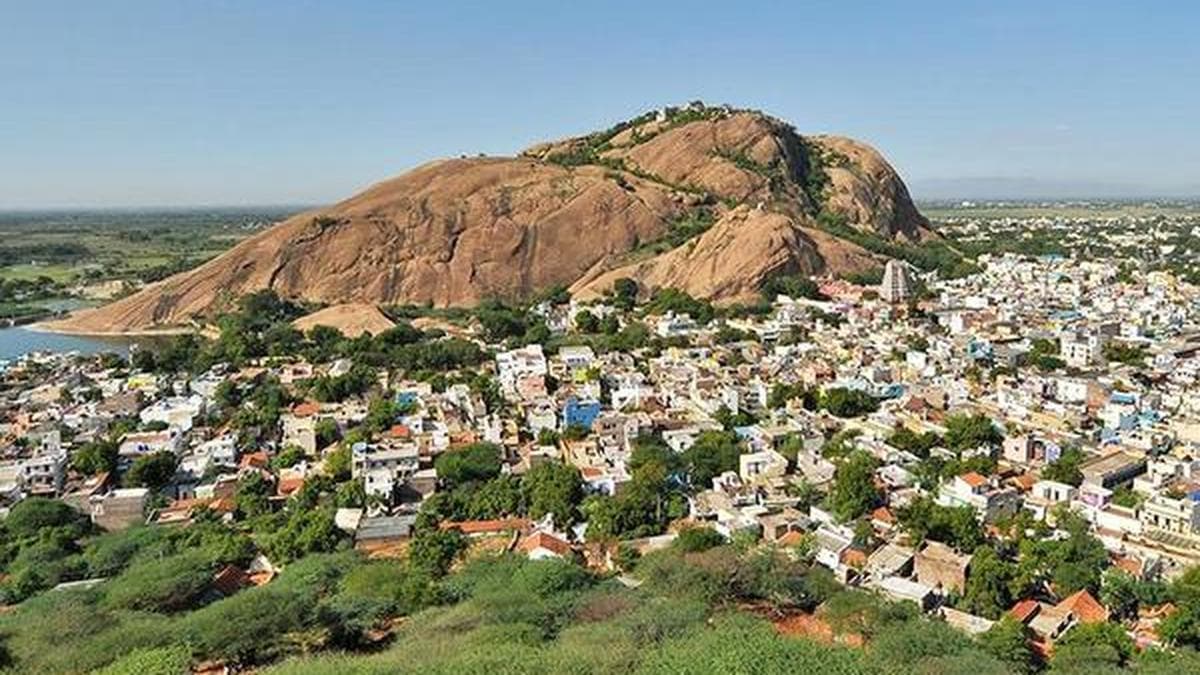

Thirupparankundram hill, located near Madurai in Tamil Nadu, is a site of immense historical and religious significance. It is one of the six abodes of Lord Murugan (Arupadaiveedu) and houses the ancient Thirupparankundram Murugan Temple. Beyond its Hindu associations, the hill also bears evidence of Jain heritage, with rock-cut beds and inscriptions dating back centuries, indicating a rich, multi-layered history. A 'deepathoon' generally refers to a lamp post, often a prominent feature in temple complexes, used for lighting purposes during festivals or daily rituals. The classification of the stone pillar as a 'deepathoon' implies a specific religious and functional identity, which could have implications for its protection, management, and associated rituals.

What transpired in the High Court was the State's admission that it lacked conclusive empirical data to definitively prove the stone pillar's identity as a 'deepathoon'. Consequently, the State declined to take a definitive stand on the matter. This position reflects the often-difficult situation faced by government bodies when historical claims or classifications arise without robust archaeological or historical evidence. It showcases a cautious approach, acknowledging the limitations of current information rather than making an unsubstantiated declaration.

Several key stakeholders are involved in this issue. The **State of Tamil Nadu**, represented by the Advocate-General, bears the primary responsibility for the protection of state-level heritage sites. Its reluctance to take a stand highlights the need for thorough investigation. The **High Court** serves as the arbiter, tasked with evaluating evidence and legal arguments, ensuring due process, and potentially directing further action. **Archaeological experts** from the State Archaeology Department or even the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) would be crucial in providing the necessary empirical data through surveys, excavations, and historical analysis. Finally, **local communities and religious groups** are often deeply invested in the classification and preservation of such sites, sometimes initiating legal action to ensure protection or recognition aligning with their beliefs.

This case matters significantly for India's broader context of cultural heritage preservation. Firstly, it brings to light the vast number of undocumented or insufficiently documented historical structures across the country. India, with its millennia-old civilization, possesses countless such sites, and their proper identification is the first step towards their protection. Secondly, it underscores the challenges in legal battles concerning heritage, where historical claims often clash with the need for concrete, empirical evidence. The State's stance sets a precedent for how such ambiguous cases might be handled in the future, emphasizing evidence-based decision-making.

Constitutionally, the preservation of heritage is a significant mandate. **Article 49** of the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) obliges the State to protect monuments, places, and objects of artistic or historic interest, declared by or under law made by Parliament to be of national importance. While this pillar might not be of national importance, it falls under the broader spirit of heritage preservation. Furthermore, **Article 51A(f)**, a Fundamental Duty, enjoins every citizen to value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture. The primary legislative framework for national heritage is the **Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958 (AMASR Act)**, which provides for the preservation of ancient monuments and archaeological sites and remains of national importance. State governments also have their own legislation and departments for state-level heritage. This case directly impacts the implementation and interpretation of these provisions at the state level.

Looking ahead, the future implications are multi-faceted. The High Court might direct the State Archaeology Department or even the ASI to conduct a detailed study to gather empirical data. This could lead to a definitive classification, subsequent protection under relevant state or central acts, and potentially influence the site's management and access. Conversely, if no conclusive data emerges, the pillar's status might remain ambiguous, posing a continuous challenge for heritage enthusiasts and administrators. This case serves as a crucial reminder for proactive archaeological surveys, detailed documentation, and collaborative efforts between government bodies, experts, and local communities to ensure that India's rich historical tapestry is neither lost to ambiguity nor to neglect. It highlights the delicate balance between religious sentiment, historical fact, and legal prudence in managing our shared past.

Exam Tips

This topic falls under 'Indian Heritage and Culture', 'Polity and Governance' sections of the UPSC and State PSC syllabi. Focus on the role of government bodies (ASI, State Archaeology Depts), constitutional provisions (DPSP, Fundamental Duties), and relevant acts (AMASR Act, 1958).

Study related topics like the functions and powers of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the concept of 'monuments of national importance' versus state-protected monuments, and the legal framework for heritage preservation in India. Understand the difference between DPSP and Fundamental Duties.

Common question patterns include factual questions on specific acts (e.g., provisions of AMASR Act), conceptual questions on heritage protection policies, and analytical questions on challenges in implementing cultural policies or the role of judiciary in heritage cases. For State PSCs, know specific sites and heritage bodies of that state.

Practice questions on the constitutional articles related to heritage (e.g., Article 49, Article 51A(f)) and their practical implications. Be ready to discuss the challenges faced by the government in classifying and protecting historical sites.

Understand the significance of 'empirical data' in legal and archaeological contexts. This term often appears in questions related to evidence-based policy-making or scientific temper.

Related Topics to Study

Full Article

Advocate-General P.S. Raman, representing the State, told the court that the State had not formed an opinion on the stone pillar, and did not wish to take a stand on the matter